By Molly Ashline

October 5, 2023

Joseph McNeil. Franklin McCain. Jibreel Khazan. David Richmond. Four young men sat down and ignited a movement. They were freshmen at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, an HBCU in Greensboro, and after making their purchases at Woolworth’s store, went to its lunch counter, sat down, and requested service. They were denied, but they did not leave. The sit-ins of the 1960s did not end on February 1, 1960, nor was it the beginning of resistance to inequality, violence, and oppression against Black people in the United States. Still, they did act as an essential example of effective peaceful protest in the Civil Rights Movement.

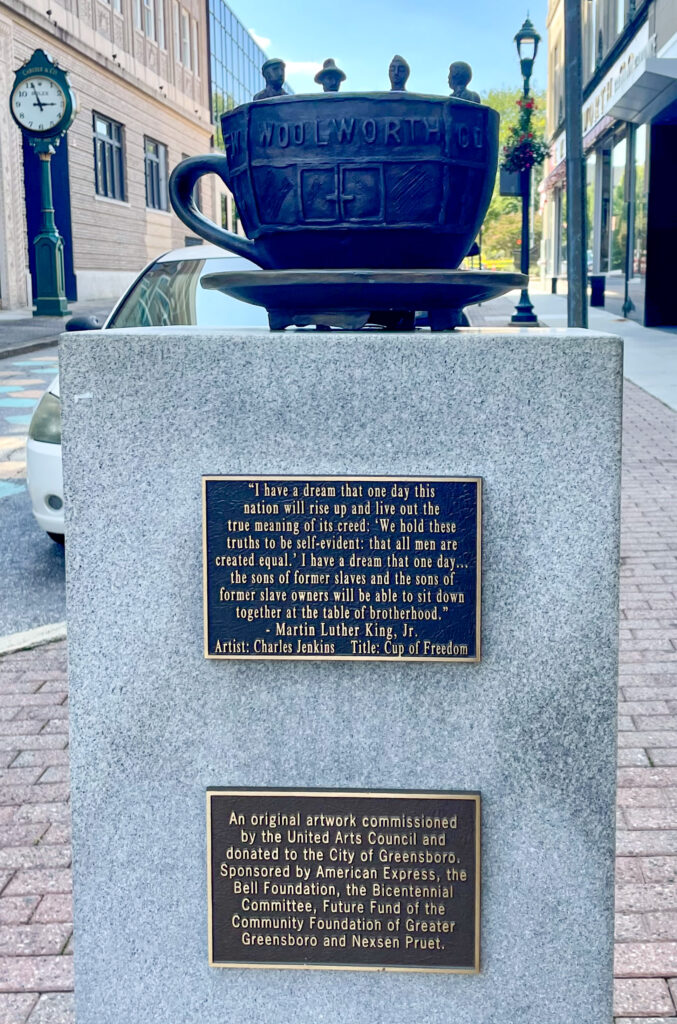

The Woolworths, where the Greensboro sit-ins occurred, is now the site of the International Civil Rights Center and Museum (ICRCM). It sits at 134 S Elm Street, at the corner of Elm and February One Place, so renamed because of that historic day. While the original Woolworth’s signs have been retained on the front and side of the building, a sleek metal sign for the center is now also on its facade. Retention and reclamation is also the case for the interior.

Upon entering the museum, one will see the spacious lobby and the gift shop to the right. Staff-guided or self-guided tours are available. Down the main hall to the left of the reception, several temporary exhibits are on display. As of the writing of this article, there is a breakdown of the language of the Declaration of Independence, an exhibition with the victims and perpetrators of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, and a regalia presentation from King Kabiru Shotobi of Ikorodu in Nigeria.

The grand staircase is on the right and leads to the center’s theater. Apart from its daily use, the theater has also been host to several panels, concerts, and lectures, either sponsored by the ICRCM or by nearby universities and nonprofit groups. Usually, the theater features a rolling film throughout the day, an example of the staff-guided tour. The film features several staff members walking through all the permanent exhibits and explaining them in detail with added context. After watching the movie, one is more prepared to enter the various spaces of the museum.

Downstairs, there is the room of shame, which is not suitable for younger children as it contains some disturbing images of the brutality of segregation and racism. Though intense, this room necessitates confronting the past (in some cases, the very near past) and the institutions and individuals that made such violence possible. It is part of the tapestry of remembrance and understanding the center offers. Past this room, the ICRCM has preserved several elements of the original Woolworths. Most notably, upstairs, the lunch counter remains fully intact. All the original stools, floors, and countertops remain. Exact replicas of the menus (five cents for coffee and ten cents for cherry pie) and restaurant equipment sit behind the counter. The stools occupied by NC A&T, Bennett College, Woman’s College, and Dudley High School students are vibrantly covered in vinyl seats, the memory of the past kept alive in the center, both good and bad. Such is the case for the rest of the museum.

In addition to the lunch counter, a replica of the dorm room in which the Greensboro Four planned the initial sit-in is downstairs, and a more extensive exhibit titled “Access Denied” is past the Woolworth’s restaurant. The entrance to this section is a replica of the “Colored-Only” doorway to the train station. It contains several smaller vignettes of segregation and integration inside with several exciting artifacts, notably a complete uniform for a Tuskegee Airman and a stethoscope and medical bag of Dr. Alvin Blount Jr., the first Black surgeon to practice at Moses Cone Hospital. There are several other displays and tiny details. One could spend hours learning here, though most spend about an hour and a half.

An impactful wall near the exhibit’s end showcases the mugshots and intake forms of peaceful protesters arrested during the Civil Rights Movement. Past this wall, there is a list of individuals who lost their lives during Jim Crow and segregation. Such is the case for much of the center. The brutality sits side-by-side with the triumphs because that is a fact of history and today’s continuing struggles. The center does not shy away from this fact. There is grief. There is catharsis. There is hope, and there is fear.

The International Civil Rights Center and Museum is a place of thoughtful remembrance. One of the most iconic and essential sites in the city, it has been maintained with care, and its complexity of history, emotion, and education highlights it as an integral experience to understanding the community of Greensboro, both past and present.

Upon exiting the museum, one can see the stretch of Elm Street to the right and left, bustling with activity. The Hopper trolley may pass by, wrapped retro to resemble the authentic trolleys that used to have lines downtown and throughout Gate City. Down the street are multiple parks, the main branch of the library, and the Greensboro History Museum. While accepting that these places and services are valuable in the city, it is essential to remember that they were not open to all equally. Exiting the center with all the lessons taught or reinforced, one may consider the issue of access. Who has access to all the resources and spaces of our city now? What barriers still exist, and importantly, how can we learn from the courage and morality of those who came before us to continue to strive for a more inclusive community? The ICRCM is a museum that teaches us history. It is not the end.